Did you know that Watchet was the inspiration for Coleridge when writing the Rime of the Ancient Mariner?

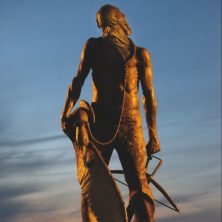

The Statue of the Ancient Mariner

‘Who’s that bloke with a bloody great seagull round his neck then?’ This was a chance remark I heard as I was walking along the Esplanade a few years ago and it set me wondering. How many people actually understand the significance of this statue and wonder why it is here?

The year is 1797 and Samuel Taylor Coleridge is living in a rented cottage in Lime Street, Nether Stowey. A few miles away at Holford, William Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy have set up home at Alfoxton. Wordsworth and Coleridge, two of our best known poets, are close friends and with Dorothy, they are all very keen on walking, particularly at night.

I mention the nocturnal walks specifically as, thanks to Dorothy who kept a diary, we are able to understand much better the poets’ habits and their time spent here in our part of West Somerset. From her diaries we know that on November 13th the three of them set off, it seems more or less on a whim, to walk to Exmoor. Berta Lawrence describes it thus: “they followed the brown track on top of the hills above Alfoxton with the scent of soaked brown bracken and dead black heather impregnating the damp air and with the cries of rooks and gulls rising from the fields below.” This does create a rather romantic scene and, with the light gradually fading, we might imagine their figures silhouetted against a milky-white evening sky. It does seem a rather strange time to set off on a jaunt but it was what they did, and often. These nocturnal habits were viewed with deep suspicion by the locals and for a time they were considered to be potential spies and up to no good, to such an extent that the government of the day employed someone to keep an eye on them. This has always amused me, imagining a character pursuing them across the Quantocks, leaping in and out of the gorse and ferns, doing his best to avoid detection.

Coleridge at this time was in his twenties, married to the long-suffering Sara and with a young son and perpetually broke. His cares and worries were at least forgotten as he and his rather lively companions made their way quite noisily from St Audries to Watchet, down Glovers Lane and into the town and harbour. There would have been nothing but a few flickering lights from the thatched houses as they progressed towards the Bell Inn, perhaps to the accompaniment of the rattling of the tall ships in the harbour and the distant hoot of an owl. There was no esplanade at the time of their visit of course, just a shingle beach and, for the most part, rude houses. The noises emanating from the long-established hostelry must have sounded very enticing on a dark, dank November night. These strange visitors were no doubt welcomed, or perhaps viewed with suspicion, but found warmth by the large open fire and ‘quaffed their ale’ in the company of the old seamen who must have frequented this place.

It is not hard to imagine that Coleridge may well have found himself in conversation with retired sailors and there is assuredly no one better at telling a tale than an old sea dog. Coleridge, on his visit to Watchet, already had the Rime of the Ancient Mariner in his mind and it was intended to be part of a combined effort with Wordsworth in their Lyrical Ballads.

So the intrepid trio spent the night in Watchet and in the morning resumed their journey. They would have been acutely aware of the activity around the harbour and it is very easy to suppose that this albeit brief stay may have given Coleridge the material he needed to formulate what has become perhaps the best-known poem in the English language.

“Merrily did we drop Beneath the kirk, beneath the hill, Below the lighthouse top”

If you have lived in Watchet for any time at all, you will be familiar with these oft-quoted lines and when a friend was visiting, she questioned: ‘below the lighthouse top? There was no lighthouse at the time of Coleridge’s visit”. She was right of course but only partly – because there was a lighthouse! To return to my description of Coleridge and the Wordsworth’s descent into the town on that November evening, greeted by just a few vague flickering lights, the most prominent beacon would have been the lighthouse on Flatholm which they would have been very aware of – a very distinctive and specific landmark for everyone and vital for shipping on the Severn Sea. Sadly, Dorothy in her journal gives no specifics of their visit but it does seem likely that the poet would have found a rich source of material here in Watchet on this autumn evening in 1797, over two hundred years ago.

The Ancient Mariner is one of the most important poems in the English language and has attracted much analysis and discussion since it was first published in 1798. It continues to do so. Its spectral qualities are a gift to illustrators and many have produced fine interpretations of the poem, none greater than Gustav Doré.

The fine bronze representation of Coleridge’s ‘Mariner’ is the work of the Scottish sculptor Alan B Herriot, commissioned by the Market House Museum and unveiled by Dr Katherine Wyndham in 2005. It is much-admired by everyone and much-photographed of course, being rather timeless in a way. It could have stood here for a hundred years or more!

“Ah ! Well a-day what evil looks Had I from old and young Instead of the cross, the Albatross About my neck was hung”

An abridged version of an article for the Exmoor Magazine written by Nick Cotton

The seven-foot high effigy of the mariner was designed and created by sculptor Alan B. Herriot, of Penicuik, Scotland, cast by Powderhall Fine Art Foundries in Edinburgh and unveiled by Dr. Katherine Wyndham in 2003.